Florida's Long History of Concentration Camps

Alligator Alcatraz is just the latest in a series of hard power installations on the peninsula

Last week, the Seminole Tribe of Florida Tribal Council shared publicly a statement to its Tribal Members expressing concern over the construction of a detention center deep in the Everglades. Until July 2, the Tribe had remained publicly silent, the Council noted, an intentional move while it explored all legal options at its disposal. Further, the Tribe signaled alignment with the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, and the Muscogee Creek Nation in opposition to what is officially named Alligator Alcatraz.

Alligator Alcatraz opened on July 1 after eight days’ construction on an abandoned jetport in the Florida Everglades—traditional home to both the Seminole and Miccosukee peoples and one of the most unique ecosystems in the world.1 According to Governor Ron DeSantis, the site will initially imprison 3,000 people and boasts 200 security cameras, 28,000 feet of barbed wire, and 400 security personnel.2 The center is not designed to be a permanent facility but instead a waystation for deportees. “Next stop: back to where they came from,” tweeted intellectual architect and Florida Attorney General James Uthmeier, who is presumably of German descent.

The moniker “Alligator Alcatraz” is claimed by the Governor to reflect the rugged nature of the Everglades, but completely sidesteps the incredibly delicate ecosystem that nearly collapsed vis-a-vis the Army Corps of Engineers and other developers beginning in the late 19th century.3 Despite this, truckloads of human beings began arriving two days before Independence Day.

However, the construction by the federal government of a concentration camp in Florida Indian Country was just the latest in a long history of imperial power in the panhandle.

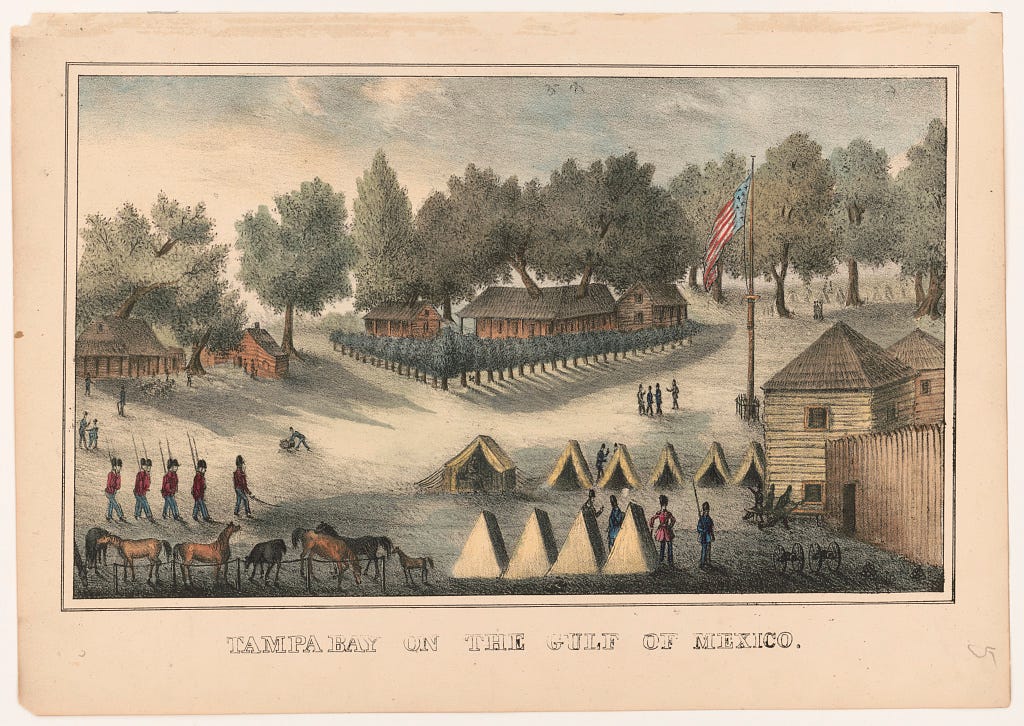

In 1824, the United States established Fort Brooke (known first as Cantonment Brooke) alongside Tampa Bay. By that time the country was twelve years into a prolonged engagement against Florida Natives that would formally last until 1858.4 Brooke’s role initially was to serve as an outpost for American military and as a check against Seminoles and Mikasukis who ventured off the new reservation that was to guarantee an era of nonviolence in Florida. But formal warfare resumed in 1835 when Seminoles and Maroons destroyed a column leaving the fort under the command of Major Francis Dade. Despite a series of early losses, the United States over the following seven years pressed against Florida Natives in efforts to finally wrest control of the lands and waterways from Seminoles, Mikasukis, and Maroons.

In addition to serving as a military outpost, Brooke served as a staging point for Americans to physically remove Florida Indians and free Blacks west of the Mississippi River. In doing so, Brooke served as the first American concentration camp in Florida. Brooke’s importance to both American removal and Florida resistance was known to both sides, highlighted by Osceola and Coacoochee’s 1837 daring move to rescue 700 Natives and Blacks at the fort while threatening the lives of anyone who dared stay. Despite Seminole and Mikasuki success, the fort remained a collection and transit point as the American military eventually overwhelmed Indigenous and Black opposition.

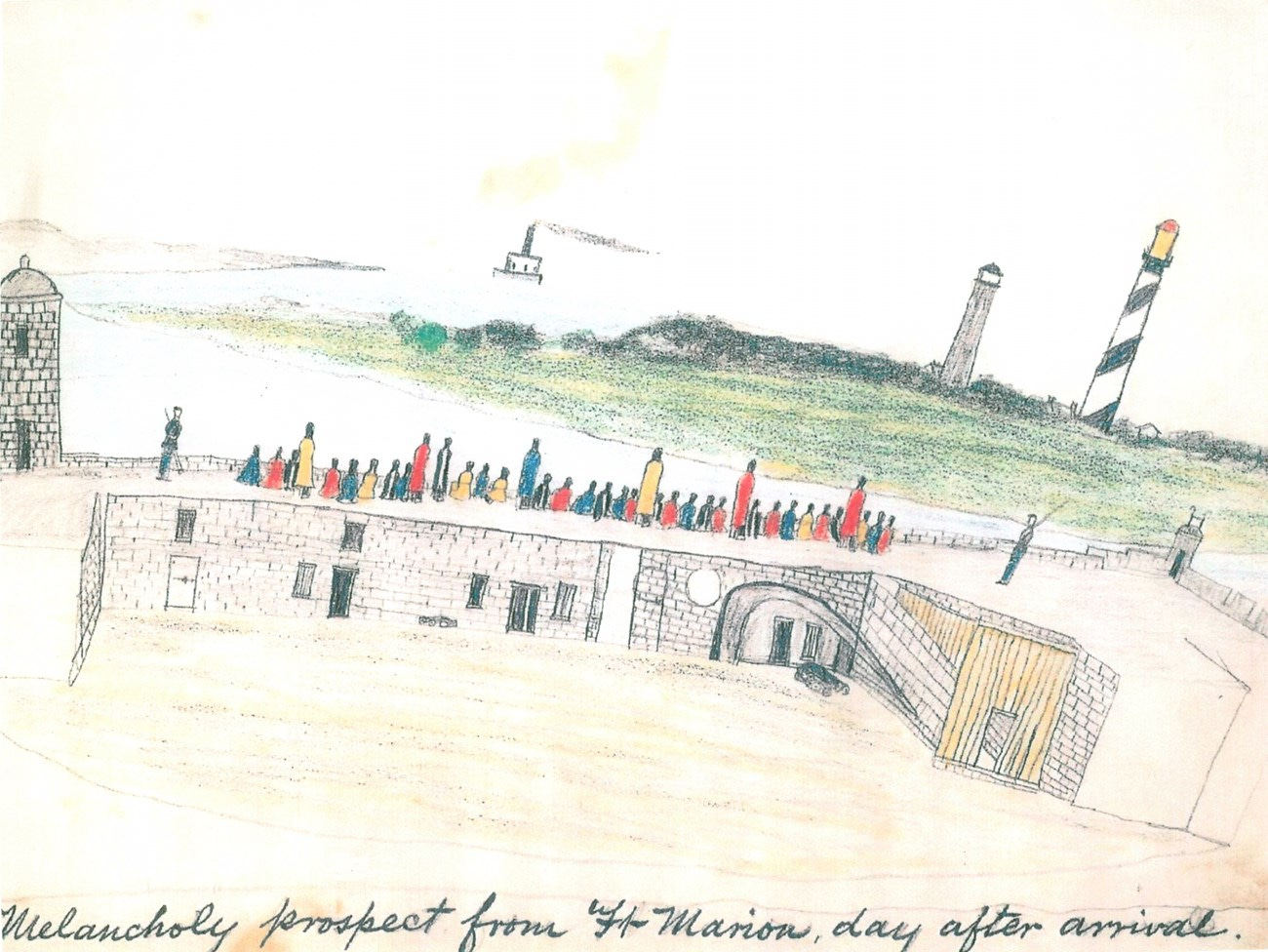

But Fort Brooke was not the only American fort used as a concentration camp during the conflict. At St. Augustine, the Americans repurposed as retitled the old Spanish bastion of Castillo de San Marcos into Fort Marion. Once designed as a fortress to protect la florida, the post in the 1830s and 1840s served in part as a concentration camp for Indigenous captives, including both Coacoochee and Osceola, the latter of whom was arrested under a white flag. According to the National Park Service, over 230 Seminoles and Mikasukis were imprisoned at the fort during the war. Americans held them under constant guard but allowed them exercise time in the courtyard. Coacoochee eventually escaped with others, but Osceola, perhaps the best known symbol of Florida resistance, was too ill to attempt to leave. He died soon afterwards at Fort Moultrie in South Carolina.5

When conflict reignited in the 1850s, the United States again created a concentration camp for Florida Natives. At Egmont Key, a small island in Tampa Bay, the federal goverment incarcerated hundreds of Tribal Members who had successfully resisted or evaded the United States until that point. The American military then forcefully deported these men, women, and children to Oklahoma aboard the steamer Grey Cloud.6By 1858, only a couple hundred Seminoles and Mikasukis remained, hiding a rebuilding their lives in the same Everglades in which Alligator Alcatraz now stands.

In many ways, Florida proved a training ground for the American military. Many of its leadership during the Plains Indian wars served as young officers during the Seminole War, including a young lieutenant named William Tecumseh Sherman, who knew Coacoochee when the latter man was imprisoned at Fort Lauderdale. So it should probably not being surprising to know that that military again called upon Florida in its pacification attempts decades later. In 1875, numbers of Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, Kiowa, and Caddo people were concentrated in the humidity and salted air of Fort Marion. Eleven years later, the United States forcibly held over 500 Chiricahua Apache Tribal Members at the site for over a year before finally moving them first to Alabama and then to Oklahoma. Memories of those prisoners in oral histories, remain etched in the walls of the fortress and in ledger art, such as Kiowa warrior Zotom’s sketching of the arrival of new prisoners at Fort Marion.

Nearly one hundred years after the Apache confinement, Florida constructed new concentration camps, this time to process Cuban refugees seeking asylum from Fidel Castro’s regime. Known now as the Mariel Boatlift, around 125,000 Cubans (along with about 25,000 Haitian fleeing Jean-Claude Duvalier) arrived on Florida shores between April and October 1980.7 While South Florida has almost always been a gateway between North America to the Caribbean and beyond, the massive influx of refugees strained American resources and forced the opening of what they called “processing centers” at Key West, Opa-Locka and Miami. Numbers of camps were eventually opened including at Eglin Air Force Base on the panhandle and a temporary facility under I-95 in Miami, perhaps most famously depicted in the opening moments of Scarface. Conditions at these facilities were difficult as Americans struggled to determine the status of these new arrivals. Despite their hardships, most Cuban emigres found new jobs within six years, elevated their pre-asylum conditions, and created new communities in South Florida. Unfortunately, Haitain immigrants struggled for a number of socio-economic reasons, though their conditions also improved in the 1990s.8

So now we turn to the Everglades, some 45 years after Mariel and 213 years after the first American invasion of Seminole and Mikasuki Country. What are we to make of this new concentration camp? Like forts Brooke and Marion, along with Egmont Key and the numbers of satellite camps in 1980, this new installation is aimed at physically enforcing who can or cannot be an American. When compared to the other installations, the racial components of American prequalification cannot be ignored, nor can the fact that this new camp sits firmly in the homelands of Seminole and Miccosukee people, despite the protests of those sovereign governments. Its presence there is a continuation of racialized selectivity that is physically embedded in the legacy of the nation’s efforts of Indigenous removal.

JWH

Thanks for reading this. If you want to support my work, you can do so by offering a paid subscription, which you can do at the button below. Thanks for being here.

For a good look at the history of the Everglades, take a look at Michael Grunwald’s The Swamp: The Everglades, Florida, and the Politics of Paradise

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/first-immigration-detainees-arrive-at-alligator-alcatraz-in-florida-everglades

More on this coming in a subsequent post.

American wars in Florida began in 1812 with the not quite unauthorized invasion by Georgia “Patriots.” https://www.ugapress.org/9780820329215/the-other-war-of-1812/

https://www.nps.gov/casa/learn/historyculture/seminole-incarceration.htm

The Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office commemorated these events and had created a digital history of Egmont Key as a concentration camp. You can view that here: https://stofthpo.com/egmont-key/

https://guides.library.miami.edu/mariel

https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332816#:~:text=Refugees%20wait%20to%20be%20processed,Photograph%20by%20Dale%20McDonald%2C%201980.

Sad and shameful, I’m not proud of the state of my birth.

Craig Pittman has called it Gator Gulag.